Explained: The story of Chagos, the Indian Ocean archipelago that Mauritius claims, UK controls

Ahead of PM Modi’s visit, India backed Mauritius’ claims over Chagos, a strategically located Indian Ocean archipelago that has long been at the centre of a dispute between Mauritius and the UK. Here’s its story.

Chagos has long been the subject of a dispute between Mauritius and the UK, which held on to these islands for decades after granting independence to Mauritius in 1968.

Chagos has long been the subject of a dispute between Mauritius and the UK, which held on to these islands for decades after granting independence to Mauritius in 1968.Ahead of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s two-day visit to Mauritius this week, India affirmed its support for the island country’s claim over the Chagos archipelago.

“We support Mauritius in its stance on its sovereignty over Chagos, and this is obviously keeping with our long-standing position with regard to decolonisation and support for sovereignty and territorial integrity of other countries,” Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri said last week.

Chagos has long been the subject of a dispute between Mauritius and the UK, which held on to these islands for decades after granting independence to Mauritius in 1968.

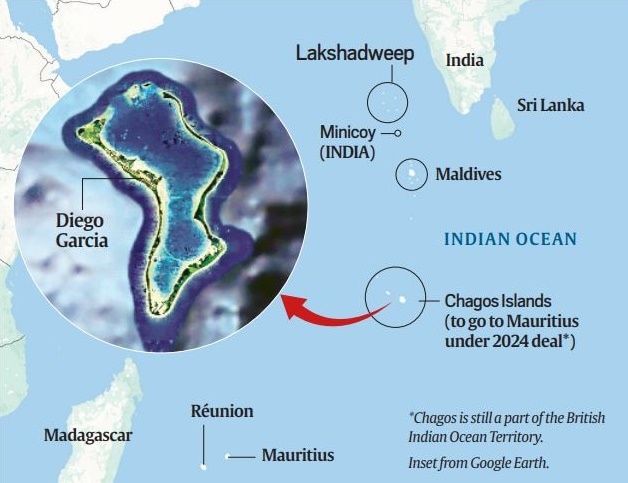

It was only last year that London officially recognised Mauritius’ sovereign rights over all of Chagos, although it retained control over Diego Garcia, the largest island in the archipelago and home to a strategically important joint UK-US military base. The deal — which awaits final confirmation from Washington — has its critics not only in the US and the UK, but also in Mauritius, and among native Chagossians.

Diego Garcia and Chagos.

Diego Garcia and Chagos.

Chagos & Chagossians

The Chagos archipelago comprises more than 60 low-lying islands in the Indian Ocean roughly 1,600 km to the northeast of the main island of Mauritius.

Chagos has a land area of only 56.1 sq km, with Diego Garcia alone spread over 32.5 sq km — which is about the same as the land area of Lakshadweep.

Including the lagoons within its atolls, however, Chagos has a total area of more than 15,000 sq km. The Great Chagos Bank, spread over 12,642 sq km, is the world’s largest atoll structure.

(An atoll is a ring-shaped coral reef, island, or series of islets, which surrounds a body of water called a lagoon.)

Although it finds mention in some Maldivian oral traditions, Chagos was uninhabited for most of its history. The islands are far from any other piece of inhabited land — its closest inhabited neighbour Addu, the southernmost Maldivian atoll, lies 500 km away — and have scant resources to support settled populations.

The Portuguese visited and mapped out Chagos in the 16th century, and used the islands as a stopover in voyages around the Cape of Good Hope to India. But it was only in the 18th century that the first permanent settlements emerged on the islands.

France became the first European power to officially plant its flag on Chagos, when it claimed the Peros Banhos island in 1744. The French had earlier set up Indian Ocean colonies in Île Bourbon (now Réunion) in 1665, Isle de France (now Mauritius) in 1715, and the Seychelles in 1744.

In 1783, a Mauritius-based plantation-owner named Pierre Marie Le Normand founded a settlement in the previously uninhabited Diego Garcia. He brought 22 slaves from Mauritius to Chagos, who became the islands’ first permanent inhabitants. These slaves likely traced their origins to Madagascar and East Africa, and were put to work in the coconut plantations in the island.

By 1786, a number of fishing settlements and coconut plantations had been established on the islands. The labour for these enterprises was supplied by slaves from Mauritius, the Seychelles, Madagascar, and East Africa.

In 1814, after the fall of the Napoleonic French Empire, France formally ceded Mauritius, including Chagos, and the Seychelles to Great Britain. After Britain abolished slavery in its colonies in 1833, indentured labour from India and Malaya was brought to the plantations.

The Chagossian population today traces its origins to freed African slaves, and the Indian and Malayan labourers who arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries. Under international law, they are the indigenous people of the Chagos archipelago.

BIOT & Diego Garcia base

In the 1950s, the US Navy identified Diego Garcia for establishing a military base in the Indian Ocean. The US initiated secret talks with the UK in 1960 — this was a time when Britain was fast shedding its once-mighty colonial empire.

After a decades-long struggle for self-determination, Mauritius became independent on March 12, 1968. But Britain kept control of Chagos, which had administratively been under the government in Port Louis for more than a century.

In 1965, the UK had created a new administrative entity — the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) — which included the Chagos islands from Mauritius, and the islands of Aldabra, Farquhar, and Desroches from the Seychelles (these were restored to the Seychelles when the country received its independence in 1976).

The BIOT was meant to provide the British (and by extension their Cold War allies, the Americans) with an overseas base in the Indian Ocean. Mauritius was paid a settlement of 3 million pounds for the detachment of Chagos.

In 1966, the UK and the US signed a secret agreement to establish a military base in Diego Garcia. The agreement included a provision that barred civilians from staying on the islands.

Over the next six-seven years, the Chagossians were expelled from the archipelago. Islanders who had temporarily left Chagos were barred from re-entering, and supplies to the archipelago were steadily curtailed.

In 1971, when the US Navy began to construct the Diego Garcia base, islanders were forcibly deported to Mauritius and the Seychelles. All plantations were shut down by 1973. The roughly 2,000-strong native population had been fully expelled by then.

The Diego Garcia base became fully operational in 1986, in time to serve as a hub for American air operations in the Gulf War of 1990-91. It also served this purpose in the subsequent American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Today, it is a crucial British-American outpost from which the two countries project power across Asia and the Indian Ocean, where China has become increasingly assertive.

The 2024 agreement

Mauritius had long claimed sovereignty over the Chagos islands, and raised the “illegal” British occupation at various international fora.

In 2017, the UN General Assembly voted to ask the International Court of Justice to examine the legal status of the archipelago. In 2019, the ICJ concluded that “the UK is under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible”.

The UNGA subsequently adopted a resolution welcoming the ICJ’s ruling, and demanded that the UK “unconditionally withdraw its colonial administration from the area within six months”.

But negotiations between the UK and Mauritius began only in 2022. A deal was struck in October 2024. Britain recognised Mauritius’ claim over all of Chagos, including Diego Garcia — however, the deal said that the UK would, for a 99-year initial period, exercise “the sovereign rights [over Diego Garcia] and authorities of Mauritius are required to ensure the continued operation of the base well into the next century”.

Mauritius could “implement a programme of resettlement on the islands of the Chagos Archipelago, other than Diego Garcia”.

The agreement was hailed as “historic” by the governments of the UK and US. But critics said the two Western powers had effectively “ceded” the control of the islands to China. In recent years, China has built close relations with many island countries in the Indian Ocean, including Mauritius.

The deal was also criticised by the opposition in Mauritius. Prime Minister Navin Ramgoolam, who was then the leader of the opposition, said the deal was a “sellout”. He has since proposed modifications to it.

Many Chagossians — living in Mauritius, the Seychelles, and the UK today — complained they had been left out of the negotiations, and had no say in how the UK-finance Trust Fund for their re-settlement would be utilised. They recall the alleged mismanagement of funds sent previously by the UK in 1972 and 1982.

More Explained

Must Read

EXPRESS OPINION

Mar 14: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05