How a relentless work ethic and an eye to bridge cultures transformed a Vietnamese refugee into Alhambra’s police chief

Timothy Vu grips the wheel of a police cruiser and casts a grim gaze south on Atlantic Boulevard in Alhambra.

He’s staring down one of the city’s most pernicious public safety issues — a long line of cars snaking down a two-lane road for nearly half a mile, frustrating drivers and endangering pedestrians.

“This is a big issue for us,” Vu said.

Vu, a 23-year veteran of the Westminster Police Department, was named chief of the Alhambra Police Department in April. That made him, very likely, the first Vietnamese American police chief in the nation.

His goals as chief aren’t sexy, but they befit the busy San Gabriel Valley town of about 85,000 with relatively low rates of violent crime. Among other goals, Vu wants to improve pedestrian safety, crack down on vehicle theft and identity fraud, and engage the community — objectives that will require officers to educate the public, show their faces in the community and get used to getting out of their police cruisers.

“Ninety-five percent of this job is just talking to people,” said Vu, 46. “The best thing we can do is get out of our car and explain.”

Police work, Vu believes, is about shouldering a multitude of modest and sometimes monotonous responsibilities.

It’s a job that he’s been training for ever since he was a boy in Orange County, the eighth of 11 children in a family of Vietnamese refugees.

Vu’s journey to police chief began on his father’s fishing boat in the choppy waters of the South China Sea off Vietnam. The family of 13, desperate to escape the turmoil of the Vietnam War, fled onto the open ocean and floated for two weeks before a Navy warship picked them up. Vu was age 3.

After short stays in temporary homes in Guam and

With so many mouths to feed, all the children worked from an early age, Vu said.

Vu’s first job was helping his mother assemble odds and ends for her manufacturing job. After doing homework, Vu and his siblings would gather in the living room and spend hours inserting a black plastic piece into another rubber piece. He does not recall what they were making, only that the family was paid by the weight, and whatever the pay was, it wasn’t much. After the work was finished, they’d gather around the dinner table, read from the Bible and sing.

His second job came at age 12, selling newspaper subscriptions door to door. He did well, and it became a paper route.

Then he stocked refrigerators at his sister’s liquor store. Next, he mixed salsa and rolled tacos at Naugles, a now-defunct taco chain. Then he sold VCRs at another sister’s video store. Then he sold clothes at Ross Dress for Less.

The jobs honed Vu’s work ethic. Everyone in the household was responsible for themselves at an early age, said his older sister Maidyne.

“There was no silver spoon for us. Nothing was handed to us,” she said. “When he wants something, he just puts 110% and gets it.”

In high school Vu worked five jobs. When he made the basketball team, he had to buy his own shoes. When he needed clothes for the high school dance, he worked extra shifts.

“You learned very early that work is the only way to get what you want,” Vu said.

When Vu was in the fifth grade, his mother suffered a stroke. Vu’s father quit his job to take care of her full time. After his older siblings moved out and with six kids still at home, everyone looked to Vu.

“He had to become the man of the house,” Maidyne said. “He was our rock.”

While Vu’s sisters went to parties and shopped for stylish clothes, Vu worked. At home he translated medical reports, insurance payments and utility bills for his father. He and his brothers and sisters helped pay the rent, did their own laundry and cooked their own meals, usually spaghetti, or Spam and rice or ramen.

His experience with poverty led Vu to pick one of the most practical of all possible futures: He would study biology at UC Irvine and become a chiropractor.

“I didn’t get the chance to think of big dreams, like going to fancy colleges and becoming this or that. I was 18 years old and helping my dad pay rent,” Vu said.

But the summer after his senior year, he got a job as an aide at the Garden Grove Police Department and was assigned to help a court liaison. One day at the courthouse he saw two men in stylishly cut suits, guns thrust in shoulder harnesses, strolling down the hall oozing “Miami Vice” cool.

The men were Orange County district attorney investigators, and Vu peppered them with questions.

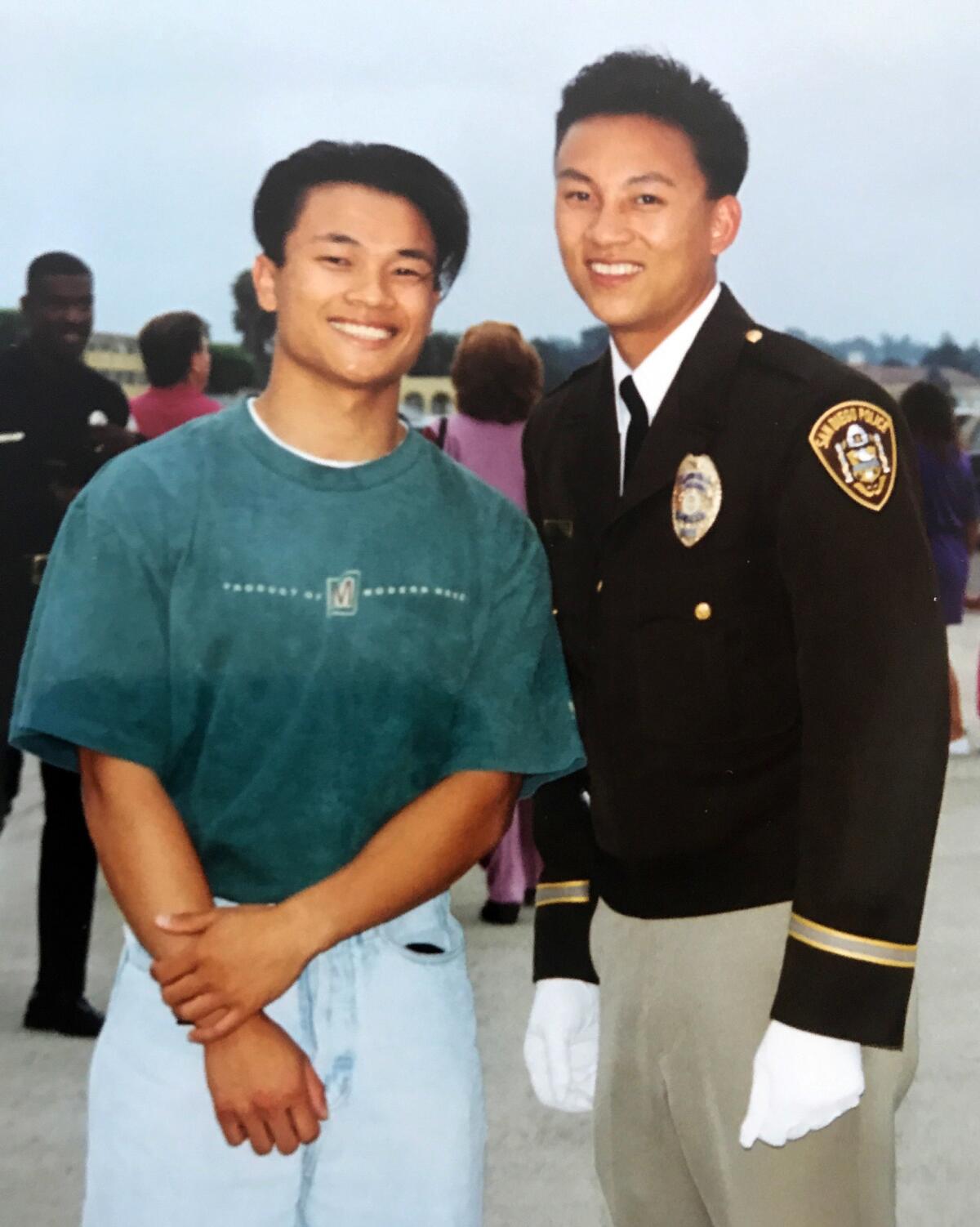

He studied criminal justice at Golden West College, and upon graduation, he entered the police academy.

After a short stint at the

He became one of the few Vietnamese faces in an agency servicing a majority-Vietnamese area.

The work ethic he learned as a child helped him rise quickly through the ranks. He became a patrol officer who was not afraid to get out of his car to talk to people. As a detective, his peers described him as a tenacious investigator who worked cases tirelessly until they were finished.

His background helped the Westminster Police Department better understand the community it was policing.

When a video store owner put up a communist flag and sparked nearly two months of protests, Vu could explain all the pain that flag had caused to police officers grumbling about being assigned to watch over the protests. When frustration built between English-speaking police officers and a Vietnamese-speaking population, Vu translated.

He also paved the way for other Vietnamese officers. When Phuong Pham, another Westminster officer, told his parents that he joining the police force, his mother wept. But Vu took him under his wing, offering career advice and encouragement.

“He was always asking me, ‘Where do I see myself?’ and trying to get me to set my goals further ahead,” Pham said.

Pham, who wants to become a sergeant, said Vu’s example has helped him imagine his own path through the department.

“For Tim to get that high up in the department for as long as he’s been in this country, that’s a huge deal for Tim and for Vietnamese people in general,” Pham said.

Vu does not speak Mandarin, Cantonese or Spanish, the languages of Alhambra’s largest immigrant populations. But he believes his years in Westminster help him understand the challenges of policing a place where nearly half the population harbors a distrust of the police.

“I’m not Chinese, but what I am sensitive to is that culture matters,” Vu said.

Chinese and Vietnamese communities, Vu finds, share many of the same misconceptions about the police. In both Westminster and Alhambra, immigrant residents are afraid to give officers their personal information because they fear it will be used to arrest them for a crime.

Victims and witnesses of crime don’t always contact the police. Officers in both cities must explain driver’s license laws, zoning laws, parking restrictions and all the unseen infrastructure of regulations that are an immigrant’s first and primary contacts with the American government.

There’s no magic solution to policing a diverse community. Only more hard work. And that’s something Vu knows well.

Twitter: @frankshyong

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.